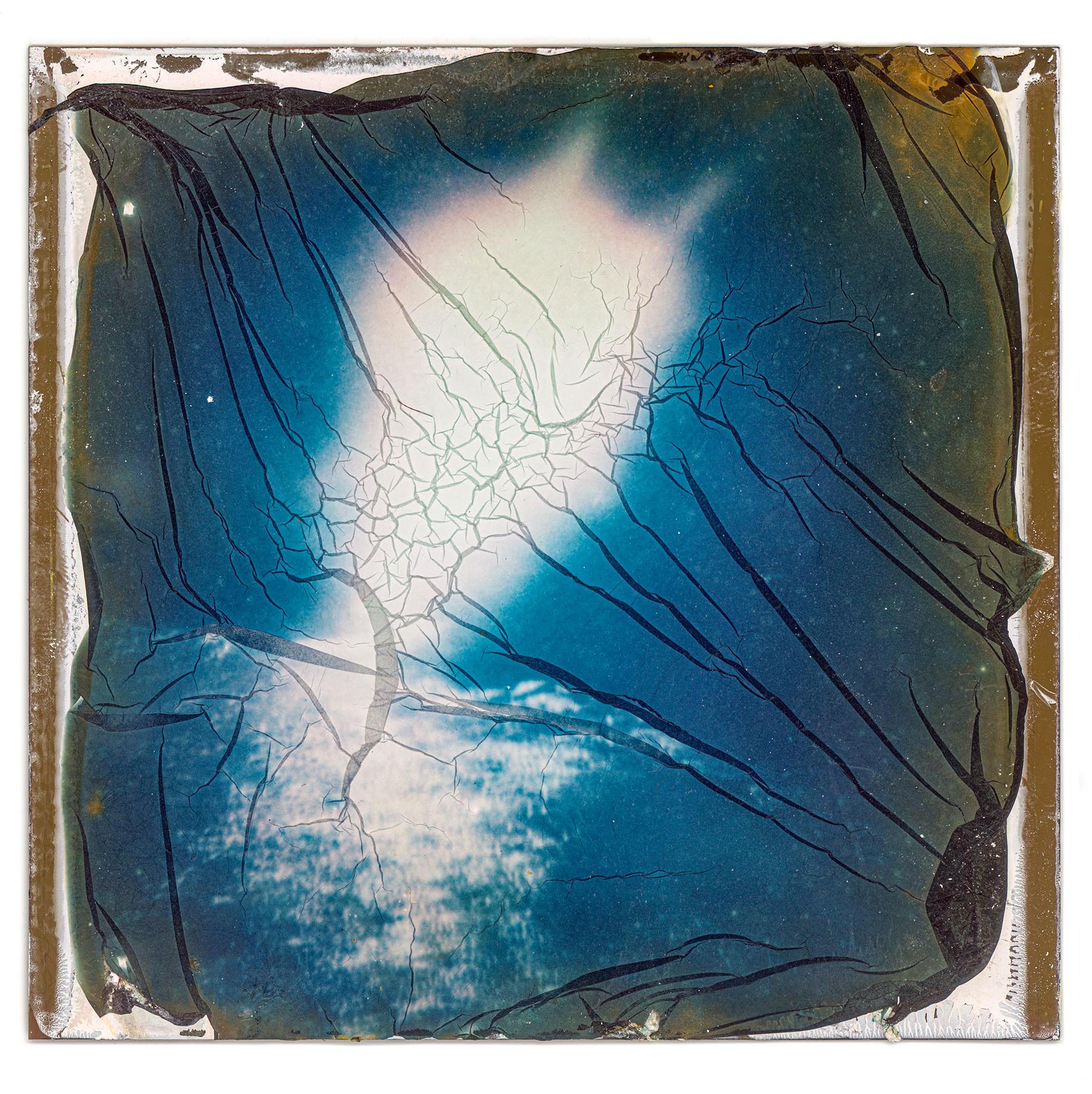

RELICS

2026

Photographing biblical events

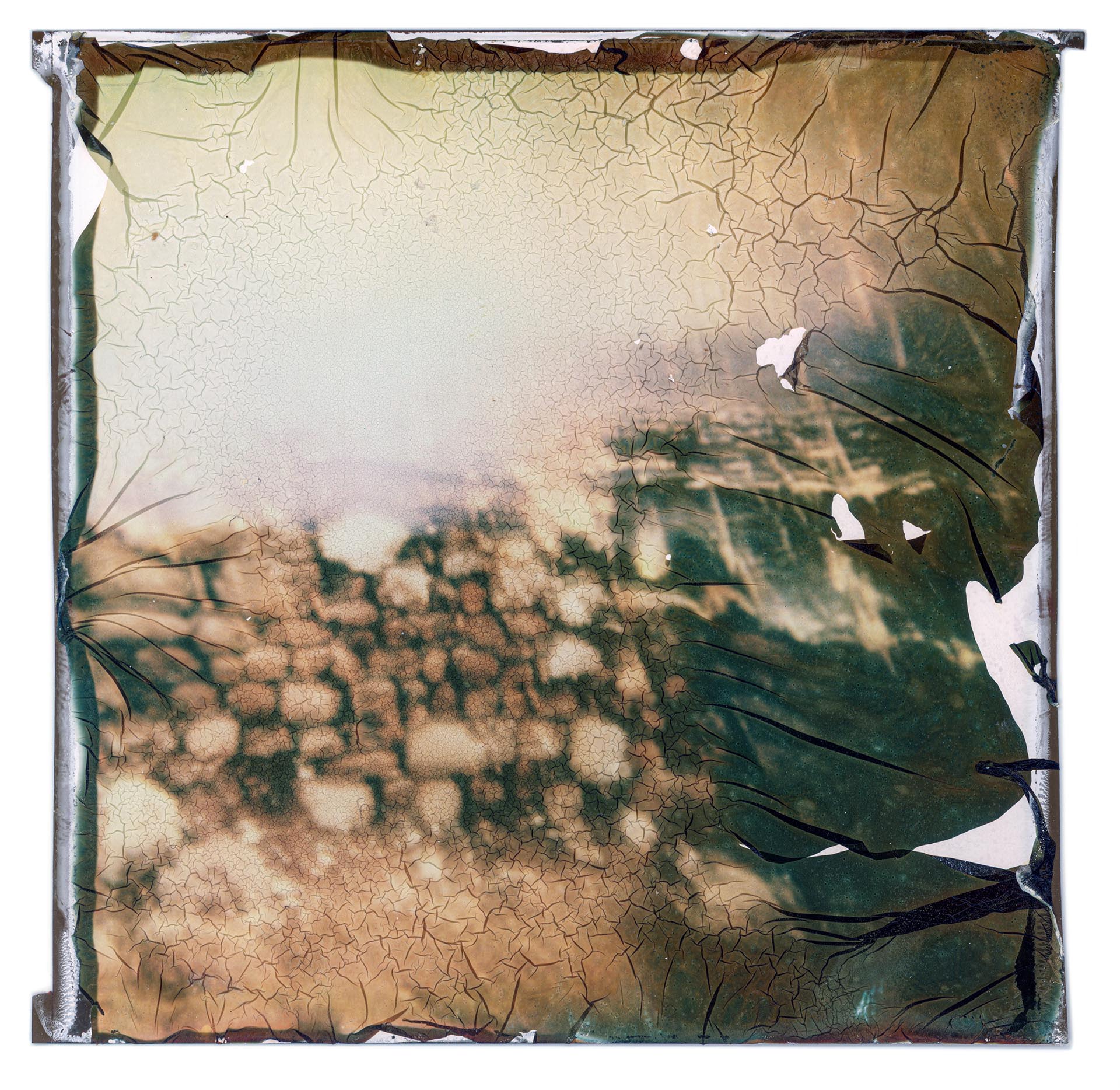

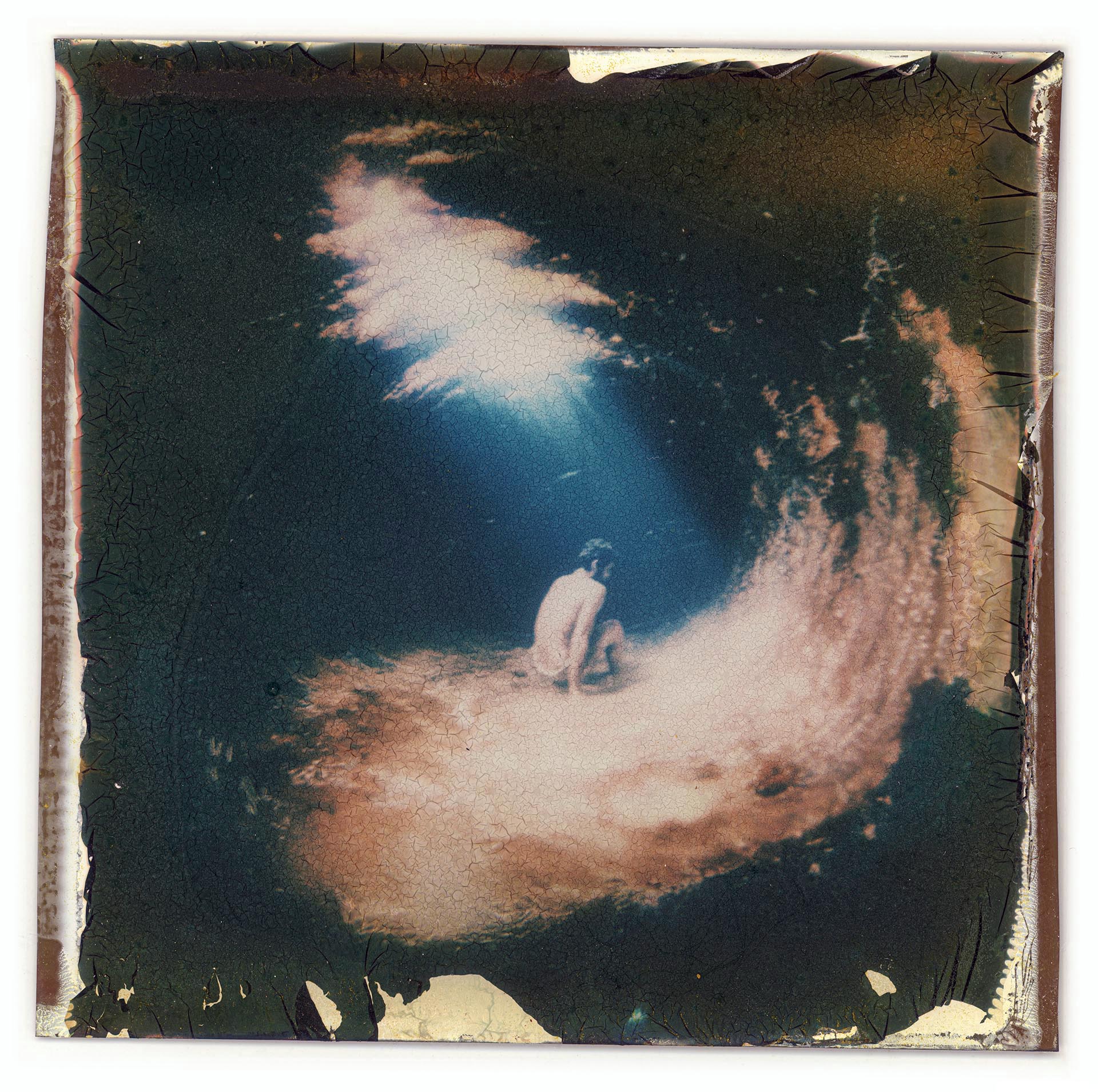

Relics is a series of Polaroid photographs depicting events from the Old and New Testaments. They present scenes that could never have been photographed, yet appear to carry the physical traces of age, damage, and survival.

The works operate in the space between photography, faith, and material culture.

Rather than functioning as documents, these images behave as artefacts and invite viewers to reflect on how faith, fiction, and authenticity are negotiated in contemporary visual culture. Particularly at a moment when the photographic image is increasingly detached from both camera and event.

Medium: Polaroid photographs, each 77x79mm

For more than a thousand years, the Biblical stories central to Western civilisation have been pictured for us. Their visual forms are so deeply embedded in our culture that it is difficult to imagine these events without recalling the celebrated paintings that have come to define them. When we think of the Crucifixion, the Annunciation, or the Resurrection, we tend to picture the compositions of Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, or Titian. Over time, these works have not simply illustrated scripture but have fixed it, replacing the events themselves with an art-historical memory that feels authoritative and complete.

What happens, then, if the language of painting, with its emphasis on style, mastery, and authorship, is set aside in favour of photography, a medium whose authority operates differently? Photography persuades not through virtuosity but through its claim to proximity and evidence. It implies having been present, bearing witness, even when that presence is impossible.

The Polaroid sharpens this tension. Its bluntness and material fragility resist grandeur and reverence. It carries none of the heroic distance of Renaissance painting. In doing so, it quietly slips past a millennium of auteurship and art-historical authority, offering images that feel less like masterpieces and more like artefacts.

What happens, then, if the language of painting, with its emphasis on style, mastery, and authorship, is set aside in favour of photography, a medium whose authority operates differently? Photography persuades not through virtuosity but through its claim to proximity and evidence. It implies having been present, bearing witness, even when that presence is impossible.

The Polaroid sharpens this tension. Its bluntness and material fragility resist grandeur and reverence. It carries none of the heroic distance of Renaissance painting. In doing so, it quietly slips past a millennium of auteurship and art-historical authority, offering images that feel less like masterpieces and more like artefacts.