Sightseeing

2019—present

Turning the act of looking into an act of creation.

Sightseeing examines what it means to see — and to be seen — in an age where vision itself is measurable. Using eye-tracking software, the viewer transforms the path of his gaze across paintings by Ellsworth Kelly into physical form. Each work translates moments of attention into laser-cut apertures that reveal fragments of the original image, turning observation into material, and time into composition. In doing so, Sightseeing revisits Kelly’s pursuit of impersonal abstraction through contemporary technology, collapsing the boundary between viewer and maker.

Lasercut acrylic cases / Archival pigment prints

Sightseeing explores my gaze by using eye-tracking software to record the movement of my eyes across different subjects. Many artists have described their works as existing only when they are seen and experienced by a viewer, and here, this idea is interpreted literally by creating a series of works through the simple act of looking.

Eye tracking is often used in scientific research, market research, gaming, and product design to determine how and where viewers’ attention is concentrated. I was interested in the philosophical implications of capturing a viewer’s gaze when looking at art and was initially drawn to the works of the American painter Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015). Kelly’s use of colour and deceptively simple shapes often belie their documentary origins, and for many years, I’ve been fascinated by his ability to transform banal details of everyday life into bold abstractions.

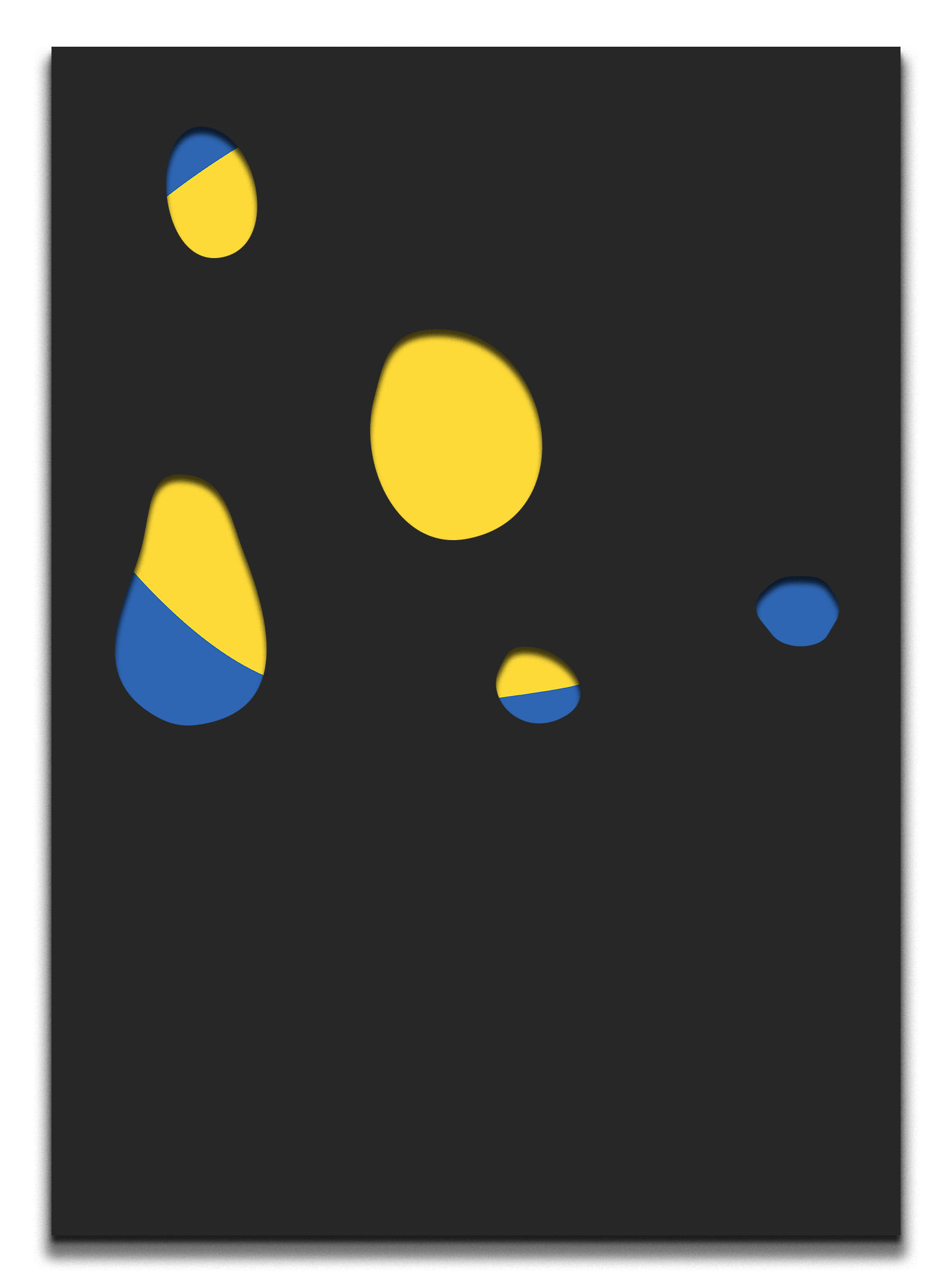

I observed a found image of Kelly’s High Yellow (1960) painting for ten seconds and encased a reproduction in laser-cut cases, the image visible only through an aperture created by my gaze. In presenting the results, the overall gaze is divided into one-second slices of time — a temporal presentation of accumulated observation, each one forming a unique abstract composition as the original image gradually reveals itself.

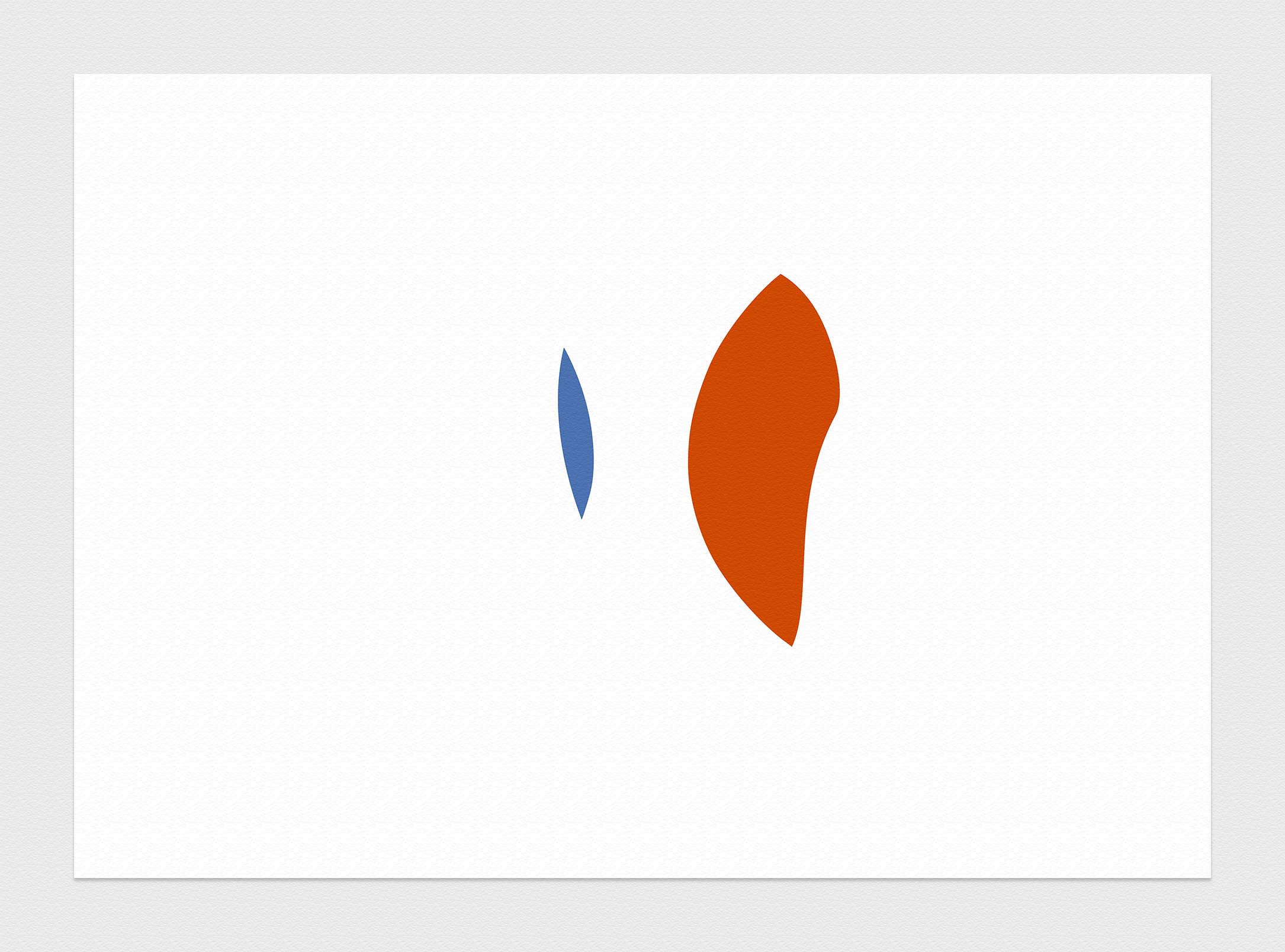

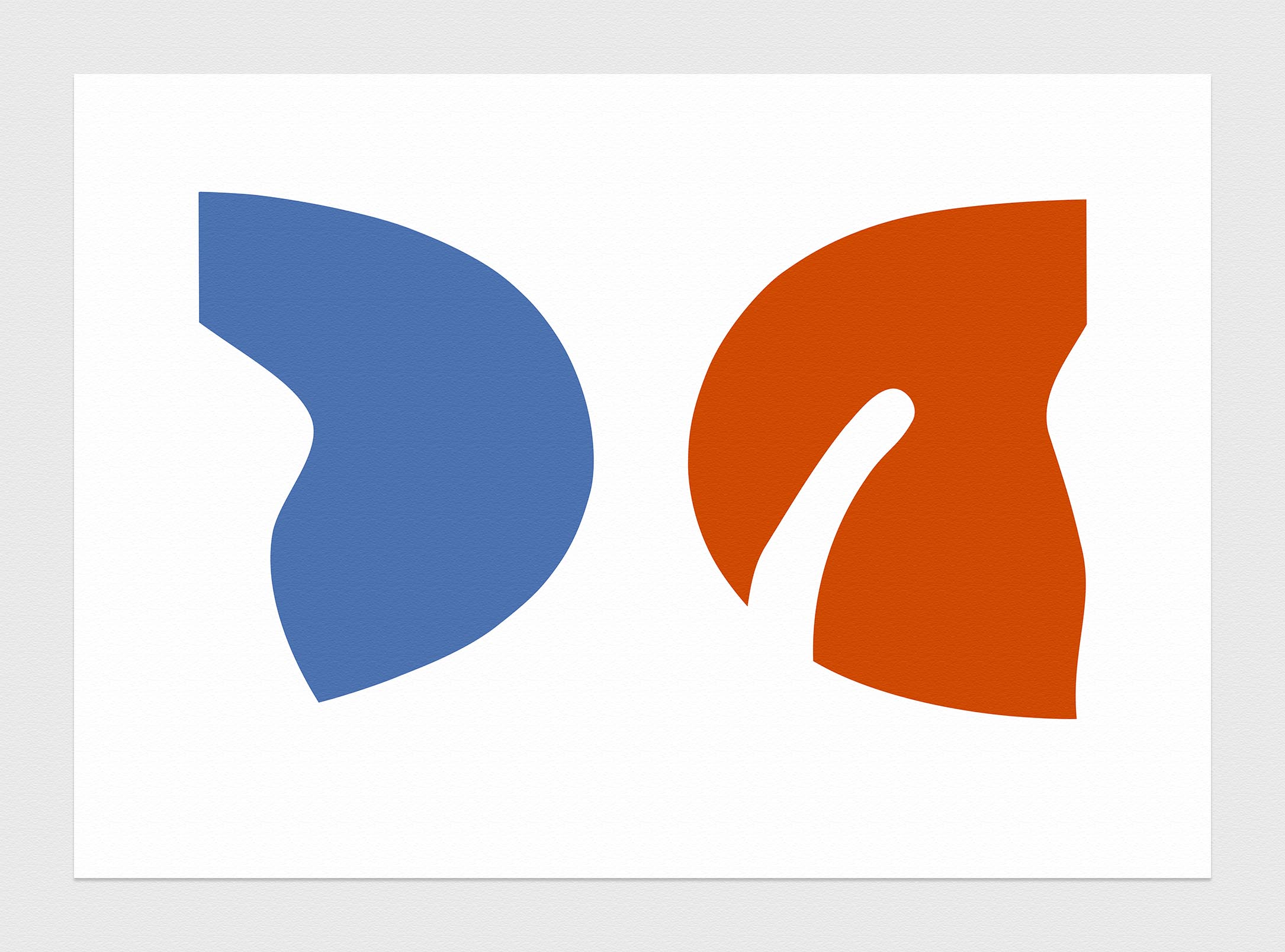

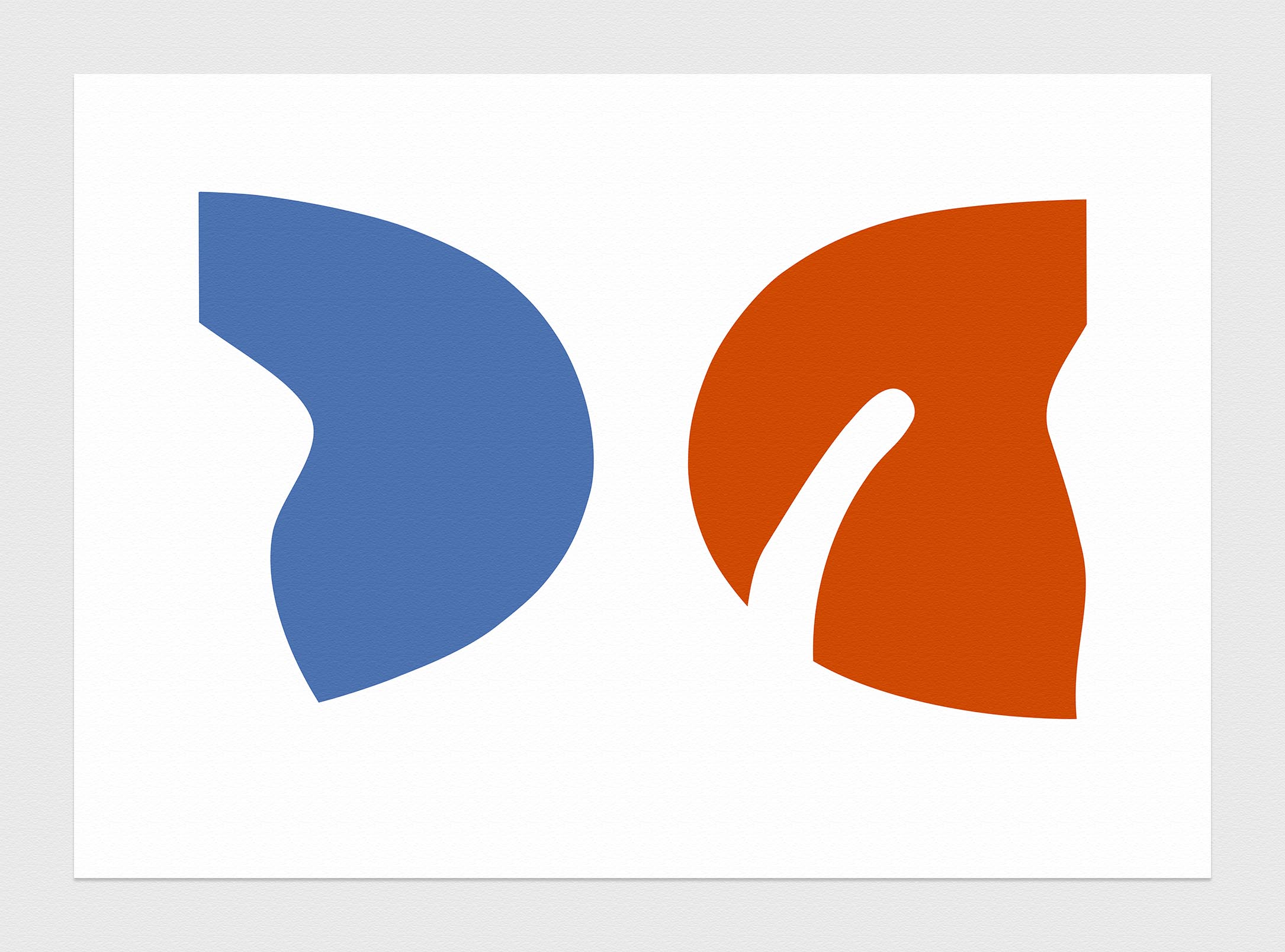

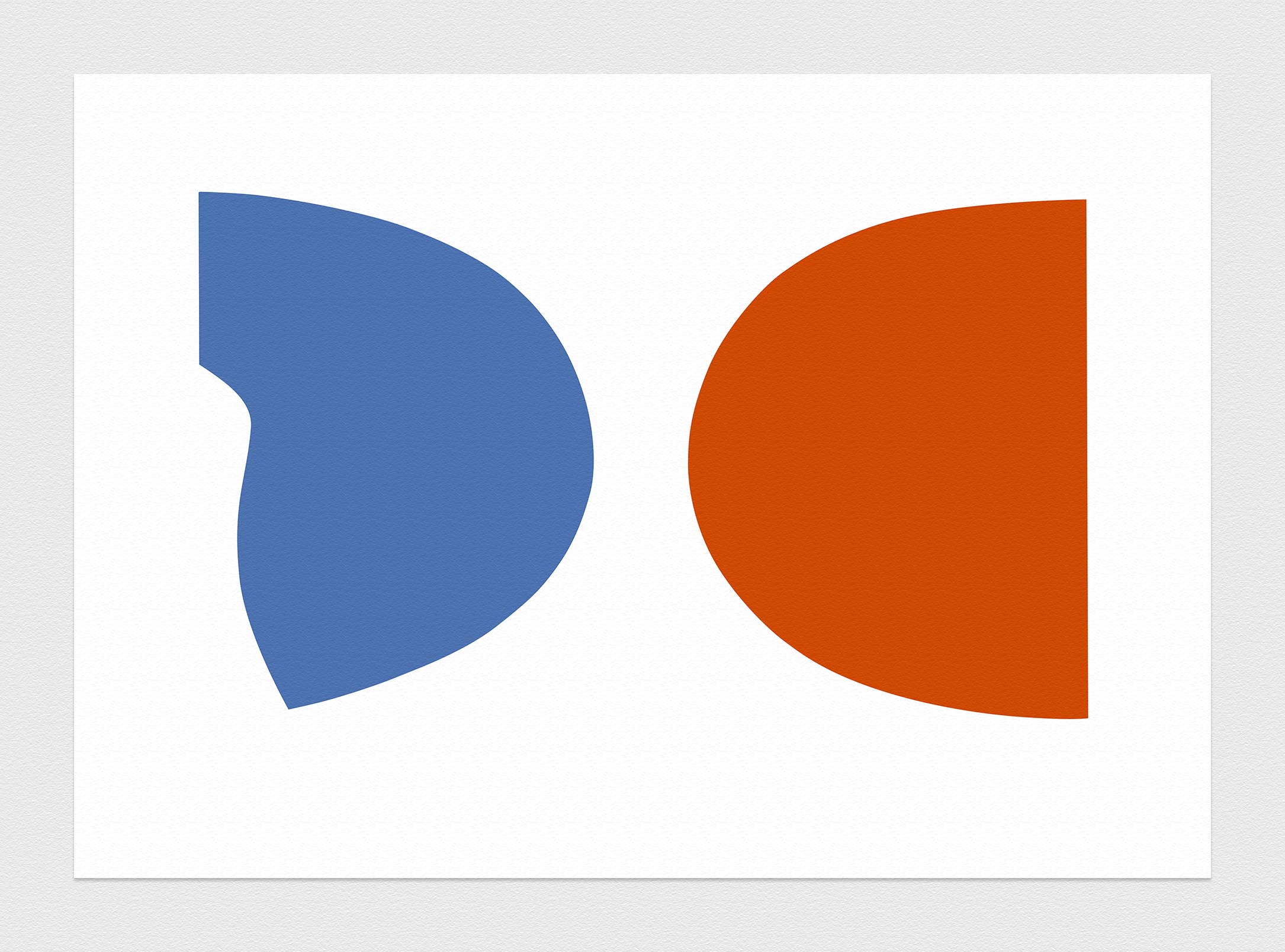

After High Yellow, I repeated the exercise with Blue and Orange (Bleu et Orange) (1964–65) and Red/Blue (Untitled) (1960). Kelly lived in Paris as a young artist in the late 1940s and early 1950s, where he found inspiration in the city’s architecture and created some of his earliest abstract compositions. Influenced by anonymous medieval craftsmen, he tried to eliminate the trace of his hand from his canvases to achieve hard-edged purity of form. I think of my use of digital eye-tracking software and laser cutting as an echo of Kelly’s method — but made with contemporary tools.

In this sense, Sightseeing is both an homage and an inversion: a body of work made not by removing the artist’s hand, but by tracing the eye — the most elusive and revealing gesture of all.

Eye tracking is often used in scientific research, market research, gaming, and product design to determine how and where viewers’ attention is concentrated. I was interested in the philosophical implications of capturing a viewer’s gaze when looking at art and was initially drawn to the works of the American painter Ellsworth Kelly (1923–2015). Kelly’s use of colour and deceptively simple shapes often belie their documentary origins, and for many years, I’ve been fascinated by his ability to transform banal details of everyday life into bold abstractions.

I observed a found image of Kelly’s High Yellow (1960) painting for ten seconds and encased a reproduction in laser-cut cases, the image visible only through an aperture created by my gaze. In presenting the results, the overall gaze is divided into one-second slices of time — a temporal presentation of accumulated observation, each one forming a unique abstract composition as the original image gradually reveals itself.

After High Yellow, I repeated the exercise with Blue and Orange (Bleu et Orange) (1964–65) and Red/Blue (Untitled) (1960). Kelly lived in Paris as a young artist in the late 1940s and early 1950s, where he found inspiration in the city’s architecture and created some of his earliest abstract compositions. Influenced by anonymous medieval craftsmen, he tried to eliminate the trace of his hand from his canvases to achieve hard-edged purity of form. I think of my use of digital eye-tracking software and laser cutting as an echo of Kelly’s method — but made with contemporary tools.

In this sense, Sightseeing is both an homage and an inversion: a body of work made not by removing the artist’s hand, but by tracing the eye — the most elusive and revealing gesture of all.

Ellsworth Kelly’s High Yellow, 1960 [Ten Seconds]Eleven lasercut acrylic cases with archival pigment print mounted to Dibond

Each 50x70cm (19.7x27.6 inches)

Ellsworth Kelly's Blue and Orange (Bleu et Orange), 1964–65 [Six Seconds]Eight archival pigment prints with signed title page

59.4x42cm (23.4x16.5 inches)

Ellsworth Kelly’s Red/Blue (Untitled), 1960 [Six Seconds]Eleven lasercut acrylic cases with archival pigment print mounted to Dibond

Each 57x70cm (22.4x27.6 inches)

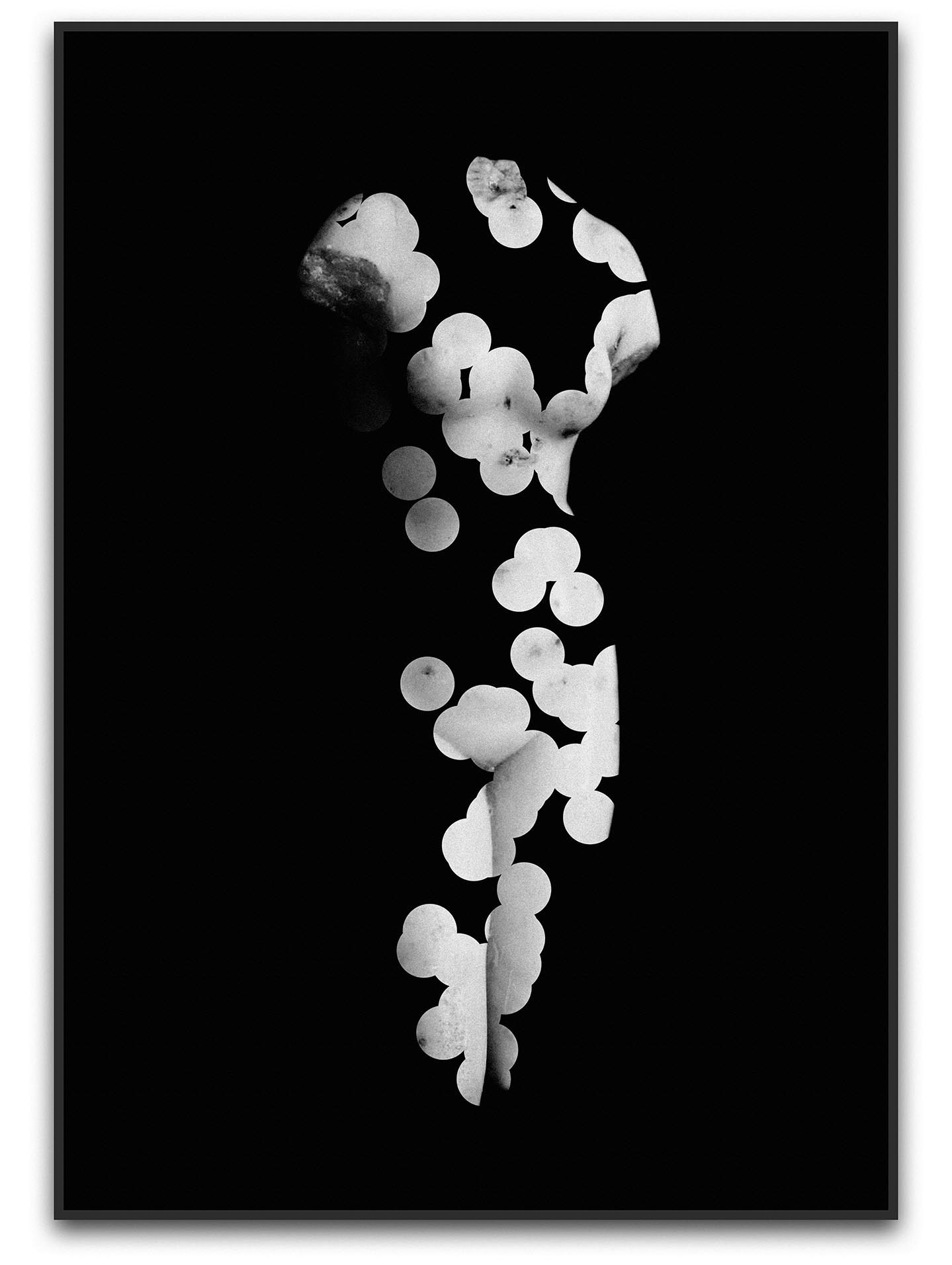

In 2019, I was approached by the New York Times Magazine to apply this method to other visual material and chose ancient marble statues of Venus. This combination of aesthetic, subject, and form results in the compression of a two-thousand year-old marble sculpture, an early 20th Century photograph, and 21st Century eye-tracking software into a single image.

Staring at Venus (2019)

Framed archival pigment print

70x100cm (27.6x39.4”)

Staring at the Torso of Venus (2019)

Framed archival pigment print

40x50cm (15.7x19.7”)

Staring at Venus (2019)

Framed archival pigment print

50x70cm (19.7x27.6”)